The success of your academic career depends on others. Let me tell you why.

Imagine this scenario: you type in a couple of keywords in a scientific database. Seconds later all of the world’s noteworthy publications on the searched topic appear in a list. The most cited publications are on top, and since you recognize one of the authors, you pick up his article, read it and eventually cite it in your own paper. This further cements the dominance of this publication in search results.

Since this author has many citations, conference organizers consider him an expert and gladly offer him to give a talk. A presentation further grows his recognition, and his professional network keeps expanding.

Because of his prominent status, students from across the world write him emails looking to join his research team. He can afford to hire the best of them because reviewers of his grant proposals also recognize his authority and trust that he can continue to deliver excellent research. Having the brightest students in his team, naturally, allows him to produce even more meaningful research.

You, an aspiring academic, maybe doing research of similar quality and importance to this superstar researcher and perhaps your papers are published in the same journals. But since your articles do not already have tens or even hundreds of citations they appear on the third page of search results. No one except your friends picks them up to read.

If only you could tell everyone about your research… Yet conference organizers do not know that you exist so instead of an oral presentation, you get a poster stand in the far corner of the dining hall simply because you paid the conference fee. Consequently, you do not get to network and are stuck with your university friends as your best collaboration partners. You miss the opportunities for joint research projects and eventually – someone else gets invited to the job interview.

The superstar effect

Economist Sherwin Rosen worked out the math of this phenomena in a paper titled “The Economics of Superstars“. He rightfully argues that:

Lesser talent often is a poor substitute for greater talent… Hearing a succession of mediocre singers does not add up to a single outstanding performance.

Rarely any profession defines “talent” as clearly as we do in the academic environment. At the end of the day, every researcher is evaluated based on the number of publications written, citations received, and grant money secured.

A researcher is a global profession. The ubiquitous use of the internet and quick travel options means that the job selection committee no longer has to settle for the local talent. They can hire the world’s best.

In a global “winner-take-all” market (as Prof. Cal Newport calls it) even a small difference in output can mean that the better academic takes it all. To have a chance of a successful academic career, you have to become recognized as one of the world’s leading experts in your field.

What causes one researcher to become a superstar while another who does similar research ends up taking second and third postdoc positions in the hope of eventually landing a permanent job?

You might have guessed from the title of this post – it is peer recognition.

The snowball effect of early Peer Recognition

In the book “Outliers” Malcolm Gladwell demonstrates the importance of early performance and the environment in forming your future.

For example, a statistically disproportionate number of Canadian professional hockey players are born in the earlier months of the year. The reason for this is that Canadian youth leagues cut off children’s training groups based on the calendar year. To the extreme, this means that the oldest child in the group is 363 days older than the youngest. At a young age, this is a significant advantage because the older kids, on average, are taller, stronger, and more agile compared to the younger ones.

The ambitious coaches mistakenly identify the physical maturity of the older kids for a higher potential in sports. As a consequence, they receive more ice time and extra coaching. Since the older kids are the leaders of their teams, they get invited to the regional and national teams where they practice together with the leaders of other teams. Eventually, because these children receive increased attention and practice with better partners, they do turn out to be the superior athletes compared to their younger teammates. What started as a small difference in the date of birth, ends up as a much higher chance of turning professional.

Similarly to the Canadian hockey players, even a small difference early in the academic career can snowball into great advantages over time. Hard work, personality, or intelligence alone are often not enough to succeed.

If we compare academic careers to the Canadian hockey system – the start of the Ph.D. is the children’s league. Everyone is equal at the outset, and only a small number will become researchers. Fortunately for us, the outcome in academia does not depend on the date of birth.

What matters is peer recognition:

- Peers will review the quality of your research and accept your publications.

- Peers will cite you in their own papers.

- You will devise new research projects together with peers.

- Other peers will judge these projects and award funding.

Demonstrating better performance early in your academic career will give you a higher chance of being noticed and hired as a postdoc at an exceptional research institution. Nobler institutions have more advanced equipment and knowledgeable colleagues. Conducting research there will allow you to devise more elaborate projects involving modern equipment, receive better advice by the water cooler, and eventually publish in higher impact factor journals.

Better institutions also attract more funding which will allow you to attend the most important conferences and get the occasional chance to present at them. An excellent presentation might then grow your professional network offering potential collaboration opportunities. It might also increase your citation count and eventually prompt job invitations to even better institutions to conduct higher quality research.

What starts as an early peer recognition ends up as an opportunity to produce higher quality research.

Research on academic career success

Measuring what exactly are the most crucial career steps to take as an early stage researcher is objectively difficult, but researchers have tried to do it at least for the parameters that can be measured. For example, a study by Laurence et al. followed 182 students into their long-term academic careers. In the absence of a better metric, their success was measured as the number of publications in their career. The results in the figure clearly show that the number of publications in the early academic career is the most critical parameter for the long term success of a researcher.

Digging into research and publishing many papers then might seem the right tactic. Although undoubtedly extremely important, in today’s competitive academic environment, this is likely not going to be enough. You might have 15 publications in top-ranked journals, but so does everyone else you are competing with for the few academic employment positions.

One parameter not considered in the study by Laurence et al. is the number of citations that a researcher receives for his articles. Citations take time to accumulate, so someone just finishing a PhD should not expect a high citation count. Later in the career, however, it becomes increasingly important. It demonstrates an appreciation of one’s work by his peers.

Perhaps even more important than the number of citations is the person’s h-index – research by the author of this measure, prof. Hirsch shows that the h-index can predict future achievements of a scientist better than the number of papers, number of citations, or the mean number of citations per paper.

The study by Prof.Hirsch further suggests that some of the researchers turning out a large number of papers but receiving few citations feel less incentivized to continue being prolific because of the impression that their work is not important. The snowball effect of received citations is thus not only an external measure used to evaluate the impact of a scientist; peer recognition can have lasting internal psychological consequences as well.

How to earn Peer Recognition

Other than conducting substantial research and writing many useful publications, what steps do you need to take to earn peer recognition?

Starting from the very first year of your PhD, you need to master networking skills, deliver memorable presentations at conferences and build a strong online presence. These skills will lay a solid foundation for your academic career. Peers will start to recognize your name, trust your expertise and deliberately search for your work. That will bring citations, collaborations, and open doors for more senior job opportunities.

Once you enter postdoc and later assistant professor’s territory, you will be expected to generate research ideas, assemble teams that can execute them, write winning research proposals and manage the obtained projects. You will also have to lecture and supervise students.

Doing an excellent job at these tasks will continue to build your recognition among peers. Funding agencies will be willing to sponsor your projects, your research partners will propose future collaborations and companies will offer you consulting contracts. Distant acquaintances might invite you to join their research project, and excellent students will ask you to become their supervisor.

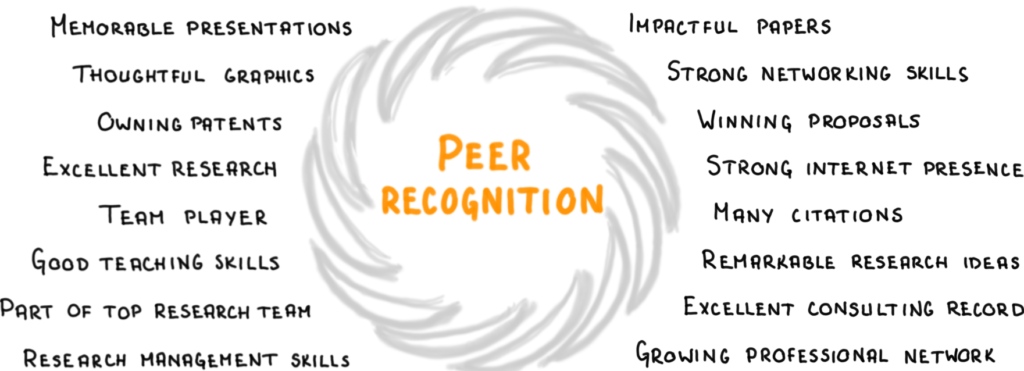

These are, of course, just some of the ways appreciation by peers will help your career. The peer recognition swirl shows the different ways in which you can earn it. Look at the figure, make an educated guess on what skills are likely to bring you the most benefit at your career stage. Start acquiring them into your portfolio one by one. Here is an article about ways to measure your success.

The more peer recognition you earn, the easier life seems. Suddenly your papers get accepted in top-ranked journals with ease (remember that peers are reviewing them). You are invited to participate in scientific committees of conferences, your LinkedIn network grows effortlessly, and conference organizers give you the stage even if you did not submit a top-notch paper.

“Stop wasting your time and get back to work”

A few established academics might feel contentious about some of the forms of peer recognition that I suggested. They might call hours of preparing to give a memorable presentation a waste of time. Or say that you should spend time in a laboratory instead of preparing a video for posting on a social network. They would claim that presentations, videos, and social networking do not count towards scientific accomplishments.

When they say “stop wasting your time and get back to work”, they have forgotten that peer recognition is what makes their success possible.

Instead of thinking of the activities for earning peer recognition as the final product, think of them as the means to customer acquisition. You will become known among peers, funding agencies, industry partners, conference organizers, and potential students. The more peer recognition you earn, the easier life will become. Suddenly your papers will get accepted in top-ranked journals with ease (remember that peers are reviewing them), you will get invited to participate in scientific committees of conferences, your LinkedIn network will grow effortlessly, and conference organizers will give you the stage even if you did not submit a top-notch paper. Through the snowball effect, all of this will eventually lead to better research.

“Ehh, it’s all about luck anyway“

Another argument that I have heard from my friends is that success depends on luck. The luck to be at the right place with the right set of skills for the right position that has opened just at the right time.

True, almost anything in life requires some dose of luck. Some of the greatest scientific discoveries, including penicillin and cosmic background radiation, have been made out of lucky coincidence. But these discoveries would not have happened if the scientists were sitting on the sofa, watching Netflix. They were out there working hard on research problems, and they had the knowledge to notice and understand the phenomena that they had luckily stumbled upon.

Sure, becoming peer-recognized will not guarantee you a successful academic career and a fulfilled life. But it significantly increases the chances of having one.

“The harder you practice, the luckier you get.”

Jerry Barber, golfer

Learn the skills

Many scientists believe that public speaking is a talent. Others assume that networking skills are something a person is born with, and yet others claim that creating thoughtful graphics requires artistic gifts. Some even think that high school literature classes were the last chance to improve one’s writing skills.

In reality, of course, these are just a set of skills, not talents that someone either does or does not have. Acknowledging that these are skills is the first step towards acquiring them. If you have read this far, I am sure you know this.

Now it’s time to get out of the comfort zone of doing research and into acquiring the skills that will make your academic career take off.

I will show you how to earn peer recognition and offer practical steps to acquire the skills to do this in the four Peer Recognized books.

A guide for writing papers that get cited

Knowing how to write research papers can make the difference between being invited to apply for a tenure track position and sending out CVs to random professors in the hope of a miracle.

Hi! My name is Martins Zaumanis and in my interactive online course Research Paper Writing Masterclass I will show you how to write research papers efficiently using a four-step system called “LEAP”. You will learn to to visualize your research results, frame a message that convinces your readers, and write each section of the paper. Step-by-step.

And of course, you will see how to answer the infamous Reviewer No.2 🙂

Author

Hey! My name is Martins Zaumanis and I am a materials scientist in Switzerland (Google Scholar). As the first person in my family with a PhD, I have first-hand experience of the challenges starting scientists face in academia. With this blog, I want to help young researchers succeed in academia. I call the blog “Peer Recognized”, because peer recognition is what lifts academic careers and pushes science forward.

Besides this blog, I have written the Peer Recognized book series and created the Peer Recognized Academy offering interactive online courses.

5 comments